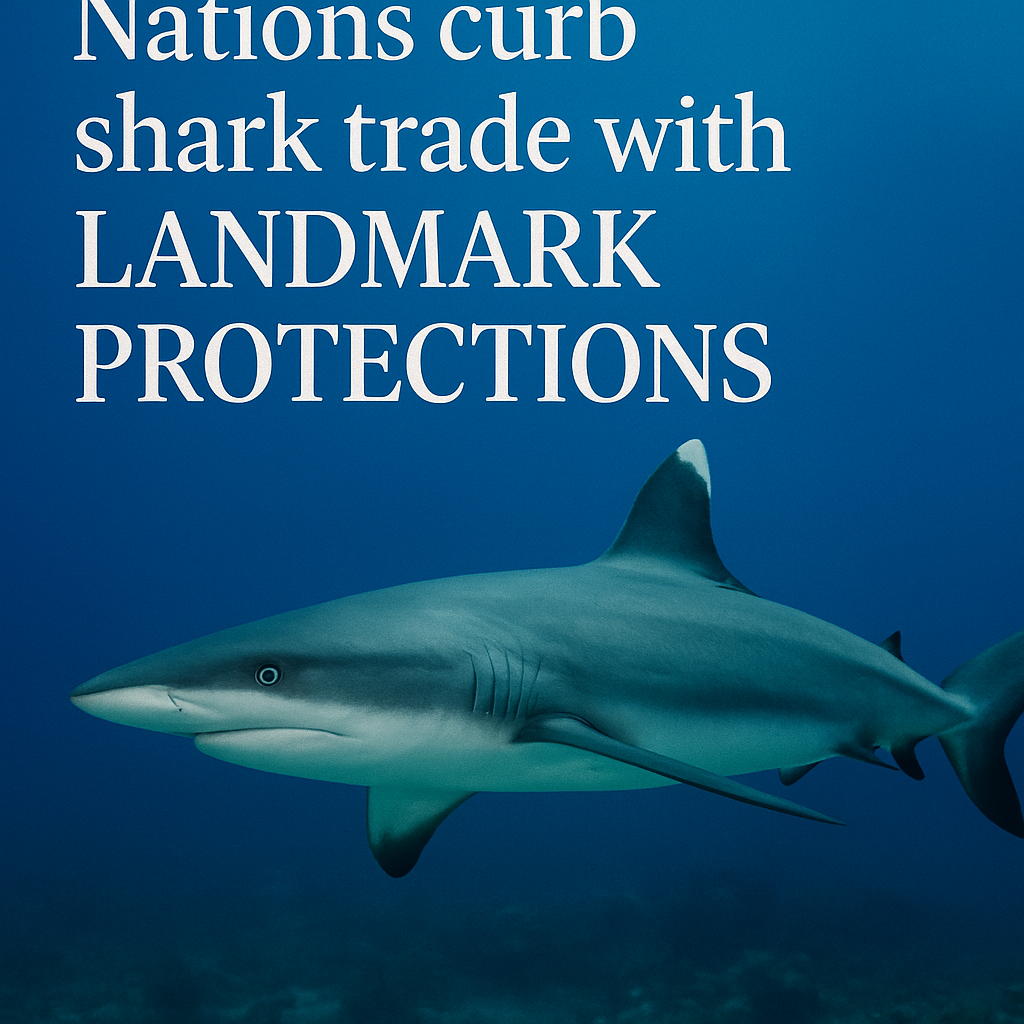

Global decision tightens trade in sharks and rays

Governments meeting under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) have moved to place broad new restrictions on international trade in a suite of sharks and rays, marking a turning point for marine conservation and seafood supply chains. At the CITES Conference of the Parties in Panama City in November 2022, parties agreed to add a number of high-risk shark and ray taxa to Appendix II — a step that obliges exporting states to issue trade permits only when they can demonstrate that international commerce will not be detrimental to wild populations.

Background: why trade controls matter

The global shark and ray trade — driven by demand for fins, gill plates, meat and cartilage — has been a major factor in population declines worldwide. Many species are caught both as targeted fisheries and as bycatch. Historically, trade hubs such as Hong Kong and Singapore have played outsized roles in the shark-fin market, while industrial fleets operating under flags of convenience have made monitoring and enforcement difficult.

CITES now has 184 party governments; Appendix II listings do not ban trade outright but require export permits and so-called non-detriment findings (NDFs) from range states. That creates a regulatory hurdle for exporters and importers, and it increases the expectations for fisheries monitoring, catch documentation and traceability across international supply chains.

Details and the regulatory ripple effects

The Panama meeting — held Nov. 14–25, 2022 — built on prior CITES action that included earlier listings for species such as manta rays and some hammerhead sharks. This latest round expanded protections to several groups of concern and prompted immediate reactions from industry and conservation groups. While environmental NGOs hailed the move as necessary to curb overexploitation, seafood exporters and processors warned that implementation complexity could disrupt legitimate trade and place new burdens on small-scale fishers.

How enforcement and compliance will work

Appendix II requires exporting countries to issue permits only after scientific authorities determine exports are sustainable. That pushes governments to improve fisheries data collection, observer coverage, and catch-documentation systems. It also increases demand for third-party verification and traceability technology: satellite-AIS monitoring from Global Fishing Watch, AI-based vessel behavior analytics from companies such as StormGeo, and DNA-based species identification services are positioned to play bigger roles. Retailers and processors — including large seafood companies like Thai Union and Charoen Pokphand Foods (CP Foods) — will need to demonstrate provenance more rigorously to avoid reputational and legal risks.

Industry and tech implications

For technology vendors the rulings are a business and product opportunity. Traceability platforms such as IBM Food Trust, Provenance and smaller specialists focused on seafood traceability are likely to see increased demand as importers attempt to meet CITES paperwork requirements. At the same time, enforcement agencies will lean more heavily on satellite monitoring and machine-learning analytics from groups like Global Fishing Watch and OceanMind to detect illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) activity.

But the transition won’t be frictionless. Many range states lack the capacity for robust non-detriment findings and rare-species identification at ports. That gap could temporarily slow exports, create bottlenecks at processing facilities, and shift trade toward countries with weaker enforcement.

Expert perspectives

Conservation NGOs such as WWF, Pew Charitable Trusts and TRAFFIC have publicly supported stronger CITES controls on vulnerable sharks and rays, arguing that trade regulation is a critical complement to fisheries management. Marine scientists have emphasized that effective implementation will require investment in fisheries monitoring, port inspections and molecular identification tools.

At the same time, fisheries industry groups warn that without capacity-building support for coastal states and clear timelines, the listings could inadvertently penalize sustainable fisheries. The consensus among policy analysts is that coupling trade measures with funding for monitoring and enforcement — and scalable digital traceability — will be essential to achieve both conservation and sustainable-livelihood goals.

Conclusion: what comes next

The CITES listings represent a pivotal policy shift that elevates trade restrictions as a lever to protect sharks and rays. Over the next 12–24 months, expect a scramble to shore up non-detriment findings, upgrade port inspection and lab capabilities, and adopt digital traceability systems. For the tech sector and seafood supply chain, the change means tighter documentation, new compliance services, and growing demand for satellite and molecular tools. If implemented well, the measures could slow declines in vulnerable species; if implemented poorly, they risk shifting trade to less-regulated channels and harming coastal communities that depend on seafood exports.

Related topics to follow: fisheries traceability tech, IUU fishing enforcement, Global Fishing Watch, seafood supply-chain compliance, CITES implementation.